ERROL MORRIS: Thank you all for being here tonight. This is somewhat strange for me. I used to say I made movies so I could talk after screening them, but now I'm writing books so that I can talk after signing them. And so it’s a great pleasure to be here. I never thought that I would be able to write a book. I had writer’s block for years and years and years and then out of nowhere, George Kalogerakis and David Shipley, editors at The New York Times, asked me to start writing for the opinion pages. And I told him I didn’t think I would be able to do it. But for whatever reason, I was. I struggled at first, but I've cranked out a whole series of lengthy essays for the Times that also includes an early version of the material for this book, Believing is Seeing. And so, I am truly indebted to the Times and to George and David for that opportunity. It would never have happened otherwise.

It’s also daunting to be here with a whole number of writers who have published many books. And now I am vestigially among them, and for that I am also truly grateful. So, thank you Harvard Book Store. Is it true that the university was named after the book store, or is this simply a misconception on my part? If so, they chose the name well. And it’s a book store, of course, that I have spent a good amount of time in, I would say, over the last 40 years, off and on. So, it’s a pleasure to be here for that reason alone. So thank you all very, very much.

I'm not sure how to handle all of this. I wanted to read from the bad reviews that have most irritated me. [laughter] But I don’t really have them on hand. People have expressed some annoyance at the obsessiveness of the book, something I have to confess I'm truly proud of. What am I if not obsessive?

It’s an odd book about photography, if that's what it’s about. Because it tries to take a series of photographs and to examine them in obsessive detail. The book opens with a story. A friend of mine, the writer Ron Rosenbaum, said to me, “Do you mean to say you went all the way to the Crimea because of one sentence in Susan Sontag?” And I said, “Well, it actually was two sentences.” True enough. And the sentences which annoyed me, and mind you I'm a great admirer of Susan Sontag, but the sentences that annoyed me described this pair of photographs that were taken in the Crimea in 1855, entitled “The Valley of the Shadow of Death.” This is a good lesson to photographers, by the way. If you're shooting a scene, don’t take more than one picture. People invariably will compare one with the other and they will jump to various conclusions of all sorts about why one is different than the other. They will ask questions, is one more authentic than the other, more truthful than the other, and on and on and on and on and on.

And my question was a very simple kind of question: how does she know any of these things that she's writing about? Is this just something that she has surmised? One of the oddities about photography, one of the things that truly fascinates me, is that people look at a photograph and all kinds of thoughts are conjured up. They may think they know what they're looking at, but do they really? After all, we're not looking at reality, at least in the case of the two Fenton photographs, we're looking at photographs of reality. What makes us think that we can transparently look through that photograph into the real world itself? I don't think we really can.

Let me just put the two photographs up, we should have at least a show and tell element here. I want to still feel connected to the visual world.

These are the two Fenton photographs, “The Valley of the Shadow of Death.” By the way, when I did get to the Crimea, this is outside of Sevastopol, it turns out that this area is for sale, actually. It may still be for sale. And I thought to myself, “Anybody can read the 23rd Psalm, but how many people can own the 23rd Psalm?”

This photograph, which I call “Off,” because there're no cannonballs on the road, and can we see the next--? And then this is called “On” because “On” and “Off” by the way, are my names for them. Cannonballs on the road. So here you have this pair of photographs and Sontag talks about how Fenton posed this photograph by placing these cannonballs on the road. And as a result, she ordered the photographs, this photograph coming after the one that you just saw before. And she insisted that this photograph was “posed.” Fenton oversaw the scattering of the cannonballs on the road, posing them for this picture.

To encourage you to buy the book, I don't want to say too much about it, it's a puzzle that was not resolved by going to the Crimea. My trip to the Crimea -- at least in terms of this puzzle, of what was going on here, that was not solved in the Crimea, even though I borrowed cannonballs from the local museum and brought them out to this location. It actually was solved by someone in the audience, Dennis Purcell, who actually lives in this area, and I thank him once again for his solution to this problem. But it made me think about posing. What are we talking about when we say that a photograph is posed? Here's my hyperbolic answer, for what it’s worth: all photographs are posed, every single one of them. Every one of them. Every last one of them. They're all posed. Maybe they're not all posed in the same way, but they're all posed.

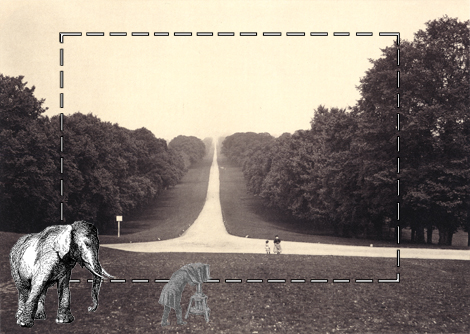

And I produced this graphic, which I'm rather proud of, I'm not sure why. It’s kind of silly. Can we put it up, please?

This is a very famous Fenton photograph and I'm asking the question that, is it possible to pose a photograph by excluding something? Say, for example, an elephant, an elephant that's standing right at the edge of frame, perhaps Fenton was saying, “Could you please keep the elephant out of the picture. I think it's really going to spoil the image.” Maybe Fenton doesn’t like the elephant. Maybe the elephant has done him an injury in the past, it's a bad elephant. And in any event, he’s just not taking pictures with elephants in them. Although there's, by the way, a very beautiful picture that he took in the Crimea of a dromedary. I'm not sure that's relevant. Just to say that he wasn’t completely opposed to taking pictures of animals. [laughter]

So yes, the example is a simple one. If you can pose something by excluding something from an image, isn’t something always excluded from every image? So, I should keep saying this over and over and over again, like a mantra. Go buy the book if you want to find out more. Let me see if there's anything that's really relevant here. Probably not. Yes, “Fenton could have had an elephant in the Valley of the Shadow of Death, plus all the workers you might imagine heaving cannonballs about. The elephant could have been walking through the frame of Fenton’s camera and Fenton waited until the elephant had just cleared frame. Click. Or removed the lens cap, the method in mid-19th century photography to take a picture. Or told Sparling, his assistant, “Get rid of the elephant.” And in that event, he posed the photograph by excluding something. He posed the photograph, but how would you know? The photograph is posed not by the presence of the elephant, but by its absence. Isn't something always excluded, an elephant or something else? Isn't there always a possible elephant? I'm looking at the back of the room. “Isn’t there always a possible elephant lurking just at the edge of frame?”

And I mentioned at the end of this, I should have written more, but maybe there'll be a second edition. We can never know for sure Fenton’s intentions. By the way, there are two great mysteries that have been so much part of my filmmaking and they're now part of my writing as well. There's the mystery of who pulled the trigger, or if you prefer, who poured the poison in the glass. But there's an even deeper mystery, a mystery that appeals to me, is the mystery of what were they thinking when they pulled the trigger? What were they thinking when they poured the poison in the glass?

The second can be a truly elusive quest. The quest for, in this instance, Roger Fenton’s intentions when he took those two photographs. But it’s an unendingly interesting quest, and we’ll talk a little bit briefly about it in a couple of other photographs that appear in this book. I think I've said enough. Let’s have another picture if we could.

Two of the chapters in this book concern probably the most widely distributed pictures in history. I don't know if you did a survey how it would actually come out, the various iconic photographs of war being usually among the contenders for that top spot. But the Iraq War produced the Abu Ghraib photographs which are clearly the iconic photographs, in my view. They will remain the iconic photographs of that war. I made a movie, Standard Operating Procedure, about the photographs and I felt that in the movie, this is a great thing about books and movies. You can publish a book after you release a movie. That I could explain in much greater detail than I could in the movie my thinking about these photographs. And although I don’t explicitly acknowledge it in the book itself, this also comes from an annoyance with Susan Sontag. [laughter] By the way, I met her several times and she is indeed extremely annoying. Even though I vastly admire her writing, I feel I have to say this lest I get myself into additional trouble.

She wrote a piece that appeared in the New York Times Magazine, "Regarding the Torture of Others," about the Abu Ghraib photographs. Basically she is saying: it’s obvious, really, what these people are thinking. It's obvious what she is thinking, these people are all exhibiting a kind of cavalier indifference, if not gloating with satisfaction, at the suffering around them. Sontag registers a level of moral outrage which I, by the way, am not at all unsympathetic with. Here’s the quote, “... the meaning of these pictures is not just that these acts were performed, but that their perpetrators apparently had no sense that there was anything wrong in what the pictures show."

Let’s put up the photograph of Sabrina Harman (taken by Chuck Graner).

She has her thumb up, and she is smiling. Next to her is the corpse of a man. But again, I wondered, how does she know what this woman is thinking? I mean, how do I know what you're thinking? I don’t. Well, there is a way you can possibly know. I can't even guarantee the end result of this kind of enterprise, but you can investigate, you can ask questions. Everybody saw these photographs, but few people bothered to actually talk to the people who took the photographs and ask them, “Why did you take these photographs? What was going on there? What did you think you were doing? What motivated this? Why are you smiling? Why is your thumb up? Who is that guy who’s dead lying next to you? Who killed him?” Questions, by the way, which I think are important. Sabrina Harman, who I interviewed in Standard Operating Procedure, very kindly gave me a series of letters which she had written to her common-law wife, Kelly. I'll read a small segment of the letter that was written on November, 9, 2003, five days after the photograph was taken.

"I'm not sure how to feel. I have a lot of anxiety. I think something’s going to happen either with me not making it or you doing something wrong. I think too much. I hope I'm wrong but if not know that I love you and you are and always will be my wife. I hate being so scared. I hate anxiety. I hate the unknown.

We might be under investigation. I'm not sure theres talk about it. Yes, they do beat the prisoners up, and I've written this to you before. I just don’t think it's right and never have that's why I take the pictures, to prove the story I tell people. No one would ever believe the shit that goes on. No one. The dead guy didn’t bother me, I even took a picture with him doing the thumb’s up. But that's when I realized it wasn’t funny anymore, that this guy had blood in his nose. I didn’t even have to check his ears and I already knew it was not a heart attack they claimed he died of. He bled to death from some cause of trauma to his head. I was told when they took him out, they put an IV in him and put him on a stretcher like he was alive to fool the people around. They said the autopsy came back heart attack. It’s a lie. The whole military is nothing but lies. They cover up too much. This guy was never even in our prison. That's the story. The fucked up thing was we never touched this guy. As soon as they released him to us, he died only a few minutes later. If I want to keep taking pictures of those events, I even have short films, I have to fake a smile every time. I hope I don’t get into trouble for something I haven't done. I'm going to try to burn those pictures and send them out to you while I'm in Kuwait. Just in case."

Now, I get a different picture of Sabrina Harman from reading that letter. It’s at the heart of what I've tried to do in my movies and what I've tried to do in this book, Believing is Seeing –– uncovering stories, hidden stories, stories that are hidden behind other stories. This is a book about stories hidden behind photographs. Stories exhumed through obsessive investigation. It’s a perfect example of what Leon Festinger called “cognitive dissonance.” People were so convinced that Sabrina Harman was as Sontag describes –– someone who “apparently had no sense that there was anything wrong” –– that they imagined that Sabrina’s letter to Kelly was a forgery. But it is not.

I'm not sure why I made Standard Operating Procedure. I had made The Fog of War with Robert S. McNamara, who was at the apex of this pyramid of power, arguably in the Johnson administration, he was the second most powerful man in the world. And this was an opportunity to interview people who were really at the very bottom, at the base of the pyramid, people without any power whatsoever, the grunts.

Now, I just have to ask you, have I said enough to make you curious about the book? [laughter]

AUDIENCE: No. We want more.

ERROL MORRIS: No? I'm trying to think, please buy the book? It’s strange, this experience of finishing a book has made me want to write others. And I even have imagined a self-help book, From Writer’s Block To Graphomania: In Two Easy Weeks, because I have contracts now on two more books –– a book on the Jeffrey McDonald case, A Wilderness of Error, which Penguin is publishing, and the University of Chicago Press is bringing out an essay that I'm expanding from the essay which originally appeared in the New York Times, "The Ashtray," which concerns an ashtray which was thrown at me at the Institute for Advanced Study by Thomas Kuhn, author of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. I assume that when the institute was set up, this was not anticipated as part of their program. So if this hasn’t put you off, you have several other books to look forward to. Anyway, I'd love to answer questions. That's why I'm here. Oh, yes?

AUDIENCE: Hi, thanks so much for speaking tonight. I think a lot of your fans, I don't know if that's the right word, would say that they can tell if one of your films is yours within the first ten minutes, maybe even if they don't know ahead of time. And so I'm interested in the way you construct a tone or a voice in a film, even though you can tell it’s a war movie, too, but that's because it’s talking all the time. You're not always there, and yet there's still a tone or a voice or something that's unique to your films. I wonder if there's any light you can shed on that, it would be great.

ERROL MORRIS: I don't know that it ever really is a conscious choice. I do know that I'm attracted to certain kinds of stories. But I would be hard pressed to tell you exactly why. I do like mysteries, difficult mysteries–– that is,mysteries that are difficult (if not impossible) to solve. And there's certain kinds of characters that I like. It seems like a terribly evasive and uninformative thing to say, but that's part of plying one’s trade, that's part of one’s art, tone. How in hell am I supposed to know? You tell me. [laughter] Yes?

AUDIENCE: Can you say why the reversal of the normal pattern of seeing is believing?

ERROL MORRIS: Why the title is Believing is Seeing instead of Seeing is Believing? Well, one seems to be far more clever than the other, although much to my chagrin it’s been used by several other writers. I felt I should read their books. One is a romance novel about a ménage à trois, which was satisfying for a short while, but quickly got kind of tedious. The other is just a straight ahead art book, not to disparage art books, but it did not seem to be terribly interesting. And the third, of course, is my effort. Why Believing is Seeing? Because we somehow think that vision comes to us in some pure native state, as if we don’t bring anything to it. It’s a reminder that what we see is often based on our preconceptions, misconceptions, we don’t come to the world as neutral observers. We come filled with bias, prejudice, vested interests of every kind. Why not occasionally be reminded of that fact? Yes?

AUDIENCE: I read your book and found it very interesting. I bought it. [laughter]

ERROL MORRIS: Congratulations. This is someone to be emulated.

AUDIENCE: I was wondering, did you intentionally pick sad things like depression and war? Were there any happy ones that you considered?

ERROL MORRIS: Ooo. The absence of happy thoughts. This actually may relate to that previous question, the question about tone. Maybe in another life, the happy life to follow, I can address those subjects. But for the time being, I think I'll stick with the sad stuff. But wait a second. Do you have a happy photograph you want me to write about? [laughter] I could do a book of the secret stories behind wedding photographs. But that might not turn out to be a very happy book. My wife and I have known each other for 40 years, but on the day we got married, she threatened to divorce me immediately after the marriage. Fortunately, that has never happened. But happy photographs? Would you be satisfied by a very sad photograph that on further investigation, turns out to be masking exquisite happiness. I could do that. Irony is also important. Without irony, what would we have? We’d have the sad residue of everything else. That wouldn't be good. Any other questions here? Yes, sir?

AUDIENCE: I love your films nonetheless often I would become uncomfortable watching them. I'm thinking back to the first, to the early ones--

ERROL MORRIS: Uncomfortable because of the seating arrangements?

AUDIENCE: Uncomfortable in a slightly more abstract sense. As I watch you interview characters who gradually reveal themselves to be some combination of deluded, foolish, perhaps slightly crazy, it seems I can't escape the--

ERROL MORRIS: Thank you for the slightly part.

AUDIENCE: I just wonder, do you feel any ethical dilemmas around encouraging people to reveal themselves in all of their warts in ways that they're unaware of?

ERROL MORRIS: Do I feel uncomfortable? I feel uncomfortable all the time. But one thing that I really, truly object to, and I've objected to it as long as I've been making movies, the idea that I'm supposed to be a social worker. And I've often thought, “You know, if I want to become a social worker, I'll go into social work.” I never saw that as part of this enterprise, making people look good or helping people. It's a different kind of job. It’s the job of capturing people, of trying to capture who they are, their complexities, how they see the world. And maybe that is an uncomfortable kind of thing, I'm not sure. But, for better, for worse, it's what I do.

AUDIENCE: You said there's no such thing as an unposed picture. What about when people aren’t aware they're being photographed?

ERROL MORRIS: Well, sometimes the posing comes from the subjects who are being photographed, and then sometimes it comes from the person who’s taking the photograph. So, it can be many different things. I gave a lecture last night, and I said that I was going to do something utterly depraved, which was quoting from my own Twitter feed. [laughter] People were writing in, they were playing stump the director. “Why do you say everything is posed? Well, how about this? How about Hurricane Irene? The camera tossed about in the hurricane winds, it travels a hundred miles and lands on some godforsaken beach in Mississippi. The shutter release is hit in that sudden landing, and a picture taken. So, Mr. Director? Is that posed?” My answer is yes. First of all, someone built the damn camera with the lens and the film and the shutter release. The picture that was taken has boundaries, it has a top and bottom, a left and right. Things are excluded. Yes, it too, is posed. I have a list which I call “Believing is Seeing Made Simple.” I thought for those people who really don’t want to read the book, I would just list a couple of things and I'm not going to read all of it, don’t worry. “Believing is Seeing Made Simple.” This seems like a good way to cut myself out of a whole number of lucrative book sales, but notwithstanding. One, all photographs are posed. Two, the intentions of the photographer are not recorded in a photographic image. You can imagine what they are, but often it's pure speculation. Three, I'm very fond of, then I'll stop. Photographs are neither true nor false. They have no truth value. None.

When I started making movies, and this is probably an extension of early beliefs that I had as a filmmaker, I was told there was a correct and incorrect way to make documentary films. There was the documentary film police. The Thin Blue Line wasn't nominated for anything. Well, it wasn't nominated for an Oscar. Yes, it did win a whole mess of awards but the Oscar committee watched ten minutes of the movie, they saw the reenactments, they heard the Philip Glass music and they figured they’d heard and seen enough. I'd like to point out that there is no correct way to take photographs or to make documentary films, or for that matter to write books. It’s not about correct and incorrect. Truth is something that you seek in what you do. You strive to understand the world around you but it's not guaranteed by style. Using available light or a hand held camera doesn’t make your work any more truthful than anybody else’s work. And I truly believe that The Thin Blue Line is proof of exactly that fact. Why do I love this movie? As an ex-private investigator, it's the best thing I've ever done, and not necessarily as a filmmaker, as an investigator of actually obsessively investigating a crime part of which was done with a camera, not all of which was done with a camera. And the investigation was good enough so that his conviction was overturned in court. And he walked out of Texas a free man. Something that I will always be immensely proud of and kind of also proud of the fact that none of it was done with cinéma vérité. That was a longwinded answer, my apologies.

AUDIENCE: I was just curious, as you're a filmmaker--

ERROL MORRIS: Supposedly.

AUDIENCE: You've made lots of films. Why are you drawn to still photographs?

ERROL MORRIS: Well, the Times asked me to write about photography, that's one thing. I know a lot of photographers, people who I really, really admire, who in turn have written about photography. Maybe the same kinds of problems about the nature of evidence, about uncovering the true nature of reality, are there in photography in some very powerful, powerful way. It still fascinates me. On one hand, let me try one other one here. The beliefs about a photograph–– this is number seven––– may change, but the underlying reality remains the same. It’s our task as in history to figure out what that underlying reality might be. And number four, which I'm also fond of, false beliefs adhere to photographs like flies to flypaper. Photography is wonderful in so many, many, many different ways. But it does allow me to–– and this may sound so pretentious and pedantic–– think about the relationship between images and reality. I find that fun.

ALEX MERIWETHER: We have time for two more questions.

ERROL MORRIS: What if they're really long questions?

ALEX MERIWETHER: We’ll see what happens.

ERROL MORRIS: Oh yes, please.

AUDIENCE: Do you like to take pictures when you travel?

ERROL MORRIS: I never take photographs. Although there are a couple of photographs of mine in the book –– my shadow in the Valley of the Shadow of Death and a closeup of my guide’s shoes –– but for the most part, I never take still photographs. Now mind you, I do work as a filmmaker, and I remember the first year when I realized I had shot over a million feet of 35 negative with maybe a little bit of reversal thrown in, so yes, I probably have taken an image or two in my day. But I've never been a still photographer. Maybe I should be, but I'm just not. If you don’t take them, can you write about them or is that bad?

AUDIENCE: If Randall Adams had not been exonerated, do you think you would have felt any differently about The Thin Blue Line?

ERROL MORRIS: You betcha. Of course I would. This is a dream of any detective, finding the evidence that shows that the man who has been convicted and sentenced to death was convicted and sentenced to death for a crime he didn’t commit. And getting the murderer, the real murderer to confess to you, this is an investigator’s wet dream. It doesn’t happen every day. It will never, ever, ever, ever happen to me again. And the fact that it happened to me once I find truly amazing and I'm grateful for it. Having said that, knowing what I know, what I knew then, that David Harris, the 16 year old kid, was the true killer and that Randall Dale Adams was the fall guy who had nothing, nothing whatsoever to do with the murder, there was this ongoing nightmare that I might not have been able to get him out of prison. I was dedicated to getting him out of prison. My wife and I were talking about mortgaging the house so we could get additional money for his defense. We were both entirely committed to seeing this miscarriage of justice righted. If I had been unsuccessful, it would have driven me crazy. It’s not something that I could let go of. I was grateful. Thank God he got out.

AUDIENCE: Was he grateful?

ERROL MORRIS: Not so much, but that's another story altogether. No, he got out of prison and he sued me, which as we all know in our modern world is an expression of deep affection. [laughter] Having said that, I would never have done anything differently. I was committed to getting him out of prison. I believed in his innocence then; I believe in it now. And I have to quote my wife again. Two remarks that I think really clarified the situation for me, this is following the lawsuit. “Thank God we don’t have to invite him to Thanksgiving every year.” And the other, which is pretty fantastic, she said, “He may be a victim, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t an asshole.”

Anyway, thank you all very, very much for being here tonight.

END