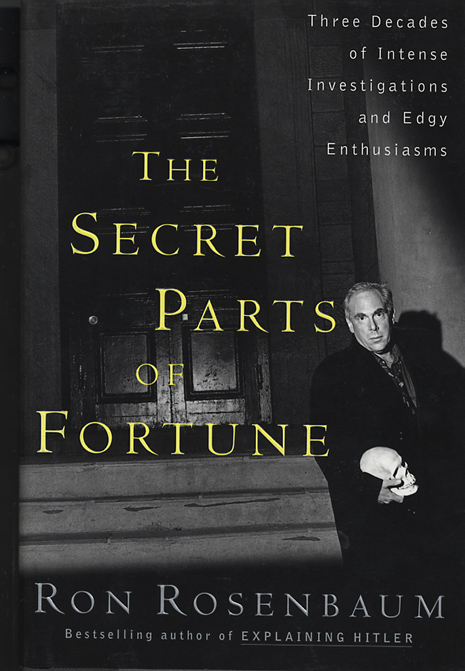

This is my foreword to Ron Rosenbaum's collected essays, The Secret Parts of Fortune. If I look like an unabashed enthusiast, it's because I am.

This is my foreword to Ron Rosenbaum's collected essays, The Secret Parts of Fortune. If I look like an unabashed enthusiast, it's because I am.Ron Rosenbaum is one of the great masters of the metaphysical detective story, a nonfiction writer in the spirit of Borges, Nabokov, and Poe. Like Poe, he can take a tabloid story (e.g., the death of identical twin gynecologists, a motel suicide, a suicide doctor) and turn in into profound and nightmarish art. And like Dupin, Poe's alter ego, he is a supreme investigator. Yet he goes Dupin one better. Poe, after all, had to disguise himself as an all-knowing detective. In his investigation of historical enigmas, Ron lays his cards on the table — his doubts about the evidence, even his doubts about himself. He appears in his own stories often perplexed, sometimes bemused, occasionally even tortured by his own investigations.

I have been reading Ron's stories in magazines for many years, but it wasn't until I saw his pieces assembled in book form that a grand scheme, a master plan became evident. This is a collection in which the many parts are great, and the sum of the parts even greater. Here is a vision, an entire cosmology, or, if you prefer, an anti-cosmology. Because the central feature of Ron's grand scheme, his master plan, is to squelch grand schemes and master plans, to defeat our natural human tendency to retreat into easy answers and bogus explanations. Many of these stories are skeptical examinations of our great need to create grand taxonomies, systems of classification that pretend to comprehensiveness. (Take Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, whose effort to provide a definitive chronology of death, has resulted in a bizarre evasion of it.) There is something immensely appealing about watching someone in combat with the world, wrestling with our attempts to understand the world, trying to talk the world into making sense of itself.

Ron provides a clue to his attitude in his metaphor of the lost safe-deposit box, a metaphor for truth that exists but truth that may be beyond our grasp. These are not essays about the impossibility of knowledge; they're skeptical and hopeful but sad. The world is crazy and its craziness propagates faster than our capacity to understand it. Borges cites a line from Chesterton: There is nothing more terrifying than a labyrinth without a center. Ron's labyrinth is a labyrinth of theories, evidence, interpretations, misconceptions, but it has a center, if not some ultimate truth then a sliver of it, a standpoint from which one can at least decide what the untruths might be.

And so the reader should look for at least three Rons in these essays.

And yet he is no glib postmodernist. There is no hint of the claim that we should give up on truth and reality altogether, that we can't possibly hope to know anything about the world when our ability to judge, to perceive, to reason, are hopelessly colored by self-interest, wishful thinking, and self-deception. His work is a powerful attempt to find a way around this dilemma. It's an attempt to recover the world by compulsively examining and reexamining our misconceptions of it.

I remember reading one of his Hitler essays and thinking, "Oh, my God, he's doing something extraordinary." And in fact, he's up to something new and unique — chronicling the way people's interpretations of themselves (and others) shape and distort what they project onto history. This is no to say history itself is subjective but to recognize the way it's often driven by subjectivity.

And so, for Ron truth exists and must be sought after, even if it sometimes can't be known with certainty. There's a terrific moment in "Oswald's Ghost." It illustrates Ron's belief that you can get so lost in a labyrinth of detail you not only lose the forest for the trees, you lose the trees as well. It's a Keirkegaard scholar-turned-private eye talks about the unreliability of evidence, the fact that some piece of the puzzle may forever be missing. Yet we continue to search for those elusive certainties, knowing that the only place to start is us — the whole mess: the evasions, the confusions, the misconceptions. Ron has made the point better than anyone else I can think of: The proper route to an understanding of the world is an examination of our errors about it.

The great Rosenbaum line, the epigram I love more than any other, the one that repeats itself in my mind again and again, is the one about the underlying mechanism of illusion and belief in the world of unorthodox cancer cures. He's speculating about the way false hope derived from bad science nonetheless seems to work miracles for many of the terminally ill. He's worried that by exposing the mechanism he's done something terribly wrong. He's giving away the game. He's depriving them of the one thing that could provide a cure: hope. And then he decides it might be OK. He can't really kill off hope because, after all is said and done, "False hope springs eternal."

Here is Ron in a nutshell. It is his version of Pandora's box: Is the hope at the bottom of the box a good thing or a bad thing? It is that admixture of principled hopefulness and intense skepticism that characterizes what he does.

Quite simply, I love Ron's work. I believe it will last. And I want everybody to read it.

—Cambridge, Massachusetts

January 2000

January 2000